“What am I? A third world lesbian feminist with Marxist and mystic leanings. They would chop me up into little fragments and tag each piece with a label.”

Gloria Anzaldúa, La Prieta

In “Trans Animisms” (2017), Abram J. Lewis shares this curious bit of gay ephemera: a Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front flyer circa 1970, inviting people to protest police brutality against Black, trans, and gay community members by levitating and disappearing the police station.

The flyer reads: “During the demonstration we will attempt to raise (by Magick) the Rampart Police Station several feet above the ground and hopefully cause it to disappear for two hours. If the GLF is successful in this effort we will alleviate a major source of homosexual oppression for at least those two hours.”

Lewis’ analysis of this insurgent levitation seeks to call into question the secular-liberal orthodoxies that impel queer/trans historians to disavow the “apparently damning specter of religion.” Another example of this sanitizing secularization is found in Reed Erickson, trans philanthropist and early advocate for trans-affirmative medical research, whose late-career interest in New Age mysticism, hallucinogens, and dolphin communication has too often tainted his legacy for trans historians. Biographies of Erickson often tether all three of these interests together in a narrative of moral and mental decline, showcasing what Lewis describes as “the interchangeability of gender transgression, psychotropics, and nonnormative religiosity in the liberal imagination.”

[To this list of things that disqualifies one from being a credible political subject, I would add any too-strong commitment to the wellbeing and autonomy of non-human animals, like Erickson’s interest in dolphins. Even today, challenging the subordination of non-human animals can be treated as a laughable, subsidiary, or impossible struggle – even among people calling for the dismantling of capitalism or the abolition of gender! Animism, animality, and abolition are intimately connected, as I started thinking about here and will continue to think about on this substack.]

Lewis calls for a “trans animism” that resists the (mutually reinforcing) anthropocentric and disenchanted underpinnings of the modern order. This is, in other words, a trans politic and history that opens up to rather than negates “other-than-human entities” likegods, demons, animate matter, and magical forces. A trans politic and history that “solder[s] trans political struggles to the powers of the inhuman,” rather than chopping and tagging, taxonomizing and disenchanting. If, to paraphrase on Angela Davis, revolution requires acting as if the impossible, radical transformation is indeed possible, trans animism asks of us: what if we could make the police station just…disappear?

(If you want a PDF of the Lewis article, email me.)

Believe it or not, this is a roundabout way of saying that I spent much of my summer locked into a combative obsession with Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949). You may have heard of it. Your mom, like mine, may have given it to you for Christmas when you were but a budding feminist. Your undergraduate thesis advisor, like mine, may have intimated that no one really reads The Second Sex, anyway.

Well, I read it, and The Second Sex revealed itself to me not just as an understandably foundational feminist text, or an unsurprisingly racist critique of patriarchy a la Tina Fey’s infamous J.Lo/Beyonce jab, but also as an extended meditation on the conjoined specters of fetishism, animism, and idolatry. Much like E.B. Tylor and James Frazer, early theorists of religion who posited animism and magic as 1) primitive responses to the natural world and 2) the roots of religion, de Beauvoir argues that patriarchy emerges from Man’s animistic conflation of Woman with Nature, and the animacy/black magic which nature mysteriously holds. This animism imbues women with an incredible amount of plasticity – they represent at once the crushing hardness of the world against which men struggle, a primal animality associated with sex and death, inert matter to be shaped by men’s will, a cultivated and ornamental artifice, and so on.

The feminist aim, for de Beauvoir, is to resist objecthood and animality at all costs, to eschew animism and fetishism, and to make a gambit for Humanity proper. She criticizes other women for submitting, even reveling, in their imposed status as an idol. Wearing makeup and constrictive fashions limits women’s capacity for transcendence, “petrifies” the face and body, and effects the “metamorphosis of woman into idol.” Butch lesbians are mutilated castrates, and femmes are narcissists who “make a religion” of their femininity. Most women, in fact, are narcissists who “soar haloed,” “at once priestess and idol,” as well as “the totem set up deep in the African jungle.” They light incense to the object that they were made into by men.

Are we starting to get the picture, here?

(Seriously, though, if I wanted to paraphrase every appearance of idol and fetish in The Second Sex, we would be here until the 5th wave of feminism.)

Germaine Greer, in the tellingly titled Female Eunuch (1970), shares many of de Beauvoir’s arguments. Greer critiques what she calls “gynolatry,” or the veneration of a cult of womanhood that is also a castrating, limiting stereotype: “the female fetish.” The only solution for de Beauvoir and Greer, if I may skew their arguments together for a moment, is the total eradication of the passivity and dependence represented by the object, fetish, and idol. To be properly human is to be an agent in a disenchanted world, “to be emancipated from helplessness and need” (quoting Greer, here)!

What’s interesting about Greer’s work is her inclusion of trans women, like April Ashley, who lost a 1970 bid for alimony because the court considered her to be a man (thus making her marriage to a man illegitimate, at the time). Greer writes, “As long as the feminine stereotype remains the definition of the female sex, April Ashley is a woman…She is as much a casualty of the polarity of the sexes as we all are. Disgraced, unsexed April Ashley is our sister and our symbol.” Under the enchantment of gynolatry, cis and trans women alike are nothing but “female impersonators,” trapped in fetishism. The object, then, is to destroy the object: woman.

“What of trans men?” you might ask. Well, they appear to Greer only as lesbians “of the transvestite kind.” Like trans women, they also represent a chafing at the limitations of “castrated” (which is to say, normative or heteropatriarchal) femininity, but their “mannishness” is ultimately an “old and ineffectual” kind of rebellion. For both de Beauvoir and Greer, gender nonconformity is infantile and counter-revolutionary, another kind of auto-fetishism to be dispelled by the feminist revolution.

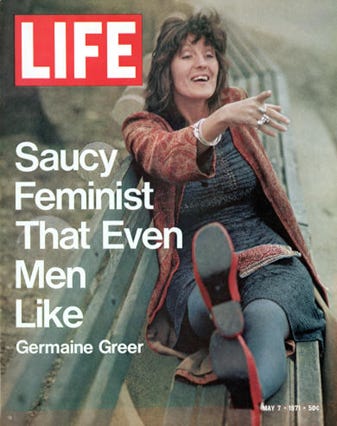

(After the feminist revolution, men will be men, and women will be Germaine Greer: a cool chick, a saucy feminist that even men like!)

Feminist revolution, for Greer and de Beauvoir, is a kind of abolition of gender, but not of sex. This abolition entails a colonizing disenchantment and eradication of queer/trans life, an empiricism both of biological sex and the secular. No African fetishes, no animism, no butch dykes or trans women. The territory of the human is demarcated: free, white, secular, cis.

“Some of us are leftists, some of us are practitioners of magic. Some of us are both. But these different affinities are not opposed to each other. In El Mundo Zurdo [the left-handed world] I with my own affinities and my people with theirs can live together and transform the planet.”

Gloria Anzaldúa, “Towards a Construction of El Mundo Zurdo”

In a time when “magical thinking” is made the culprit of social and environmental ills, trans animism is a challenging call to answer. How do we grapple with the appearance of miracle in the histories we tell and identify with? Consider that Reina Gossett reports that in Los Angeles in 1970, protesters succeeded in levitating the police station 6 feet from the ground. How do we organize, some of us leftists, some practitioners, and some both? What are our potential political tactics?

In the least, trans animism calls us to cultivate a view from the left-hand (which is not the same thing as the Left), from the perspective of all that is disavowed from the modern humanist subject: animals, gods, objects, matter.

What kind of thing will we be in a world transformed? What does a trans*feminist politic of the fetish look like? Perhaps we can’t know for sure until the transformation has already begun, and perhaps the religious view of trans animism grasps this aspect of all abolition most fundamentally. New world coming, El Mundo Zurdo.