My (Ghost) Adventures with Men

somewhere Zak Bagans is getting a chill

Sometime last year I was at a friend’s birthday party, doing something I haven’t done in years: talking to a group of straight men. This is not an area in which I typically excel, so when one of them mentioned a recent paranormal experience, I latched onto it. Do go on, sir! We must hear it! (This will kill some time!) He led the gathering crowd (of three) into another room. A space only for the initiated. After setting the scene—he was in a field at night, or something like that—he played us some crappy distorted audio recorded on his iPhone. He then testified to the psychological wonders of shrooms, which apparently, he had been drinking in his tea throughout the entire conversation.

I then sat, feeling simultaneously curious and captive, through a conversation among the men about psychedelics and life’s strange synchronicities. Another dude shared that his mind had likewise been opened to another, perhaps paranormal, layer of experience, revealed in moments like the microwave timer going off at the same time as a song ending. He also saw hidden movements of the eerie in having a conversation with a woman, tuning out, and then realizing that he had missed something important that she said. Uncanny, indeed.

In one sense, this is an ordinary story about getting stuck in insipid chat at a party. And yet, as much as I was dying to get out of there at the time, in retrospect I’m interested in how the conversation became a kind of ritual space in which events and their significance were experimentally and collectively reconstructed. The use of psychedelics and the practice of sharing spooky stories in a circle become two techniques of shaking life’s otherwise meaningless stuff through the sieves of “synchronicity” and “the paranormal.” The ritual opens the possibility for seeing, perhaps creating, life anew. A dude who microwaves noodles and doesn’t listen to women becomes a seer of ultimate things.

What do paranormal stories and rituals of story-telling do? Other, smarter people have written about this in various ways (here’s one great example). But if you will indulge me as the dilettante that I am, I want to make some suggestions about what these stories do for a certain kind of masculinity, as it’s displayed in the party story and the paranormal reality show Ghost Adventures. Of course, the paranormal experiences recounted at that party were hardly adventures—they were hardly even events. But the very tedium of this encounter, the boringness of the stories shared, makes me re-view Ghost Adventures as a ritualized space enabling something that is also absolutely mundane: men feeling things.

I would call Ghost Adventures my guilty-pleasure TV if I had any high-brow pleasures, but I’m not sure that I do. As the title sequence reminds you at the beginning of each episode, the show follows host Zak Bagans and his team of paranormal experts as they search for evidence of ghost activity in all the familiar haunted spaces: mines, saloons, castles, abandoned hospitals, and just plain creepy houses.

Ghost Adventures might be dismissed as the worst kind of hokey paranormal pulp, or the all-too-familiar display of white men ‘roided, Red-Bulled, and red-pilled up. And in a way, you wouldn’t be wrong. The show is quite often just footage of these men yelling “Dude!” at each other and full English sentences at medieval Romanian ghosts. Our intrepid host Zak might also seem like a garden-variety douchebag: half magician-adjacent pickup artist, half Christian fitness influencer. You wouldn’t be wrong there, either.

But what interests me is that the show is both premised on the impenetrability of heteromasculinity (symbolized by Zak’s muscular form and imposing stance, the all-black uniform, the thick armor of tech, the “Chillin in the Hot Tub” energy of the team’s interactions) and the spiritual porosity and vulnerability of these men. They, like the party dudes, must be sensitive, attuned.

Although their investigations theatrically employ the latest in ghost-hunting tech—spirit boxes, EVP recorders, electromagnetic field detectors, infrared cameras, thermometers, mel meters, etc.—the body and its sensations are often the more frequent and reliable media for detecting presence. When Zak feels cold or hot, a spirit is there. When Zak feels hair standing on end or goosebumps, a spirit is there. When Zak feels pain or dizziness, a spirit is there.

Almost any episode will demonstrate that spirits also live on in the emotions of these men. Zak is often overtaken by fits of rage, and sometimes the urge to hurt his beta male co-investigator Aaron. Other times, Zak and Aaron report sudden feelings of fear, anxiety, or intense sadness. At least once an episode, it seems, Zak forces Aaron to be alone in some abbatoir or crumbling well until he totally breaks down. In one case, after his isolation Aaron is moved by a spirit to say “I wanna kill Zak Bagans.” Time and again these affects are taken to be, in fact, effects of spirits communicating (if not toying) with them.

A skeptical viewer would say, dude, of course you’re feeling weird, and it has nothing to do with “ghosts”! You’re wandering around a creaky ship or a drafty castle at 4 am with all the lights off! Your bro is hurting your feelings! What was the last thing you ate, by the way?

And yes, when I watch Ghost Adventures, I think these things. I shout them at my TV. But even if we totally bracket the question of whether ghosts or other paranormal entities exist, there’s something missed by simply shelving the ghost adventure as bad, brainless, brute TV. We would miss what is being created anew in each episode.

The ritual of the ghost adventure (orchestrated by the testimonials, by the darkness of the night time, by the technologies in use, by the generic conventions of the television show) creaks open a gap for these men, in which they can feel. They feel fear and sadness. They articulate grievances and conflict. They inhabit their bodies as sites of vulnerability and affectability rather than sheer, muscular capacity. Their display may be a little ridiculous, but it’s no less serious for being so.

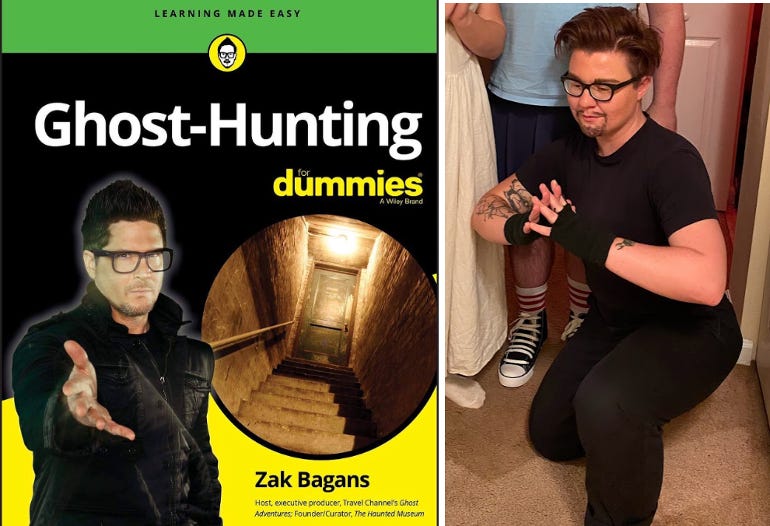

There’s something deeply amusing, even hilarious to me about certain genres of white masculinity. And terrifying! I love watching Ghost Adventures. I find Zak’s machismo so perversely charming and campy that I drag-kinged him for Halloween. And yet, sometimes the thought of these volatile bros being real men in the world gives me shivers as I watch. The affective possibilities furnished by the paranormal may not be good ones, after all.

Judith Butler tells us that “Laughter in the face of serious categories is indispensable for feminism.” I don’t think she means only that laughter can deflate, demystify, or disempower its object. In laughing at these ghost adventurers, these men who shout in the dark or tell tales in cramped rooms at house parties, I don’t mean to suggest that there’s obviously nothing going on here, or that it’s obviously just men discovering their own emotions in the flimsy mirror of the paranormal. This would be yet another serious categorization, a “common sense” response that assumes the possibility and responsibility of cleaving apart human actor and extrahuman forces, paranormal and patriarchal, humor and terror. Things are rarely that simple.

Stories, laughter, and ghost-detecting technologies are all ways of feeling our way through the utter weirdness, dependence, and discomfort that is often the everyday experience of being a human. In writing this, I myself am stretching Ghost Adventures and a totally random conversation until they touch each other, and then I turn that contact into evidence of the way the world really is. In scoffing at “synchronicities,” I nevertheless end up with my own. As Zak says at the beginning of every episode, “There are things in this world that we will never fully understand.” And yet that very opacity seems to enable the constant work of understanding. And that is the work of speaking, to men, at parties.