rabbit lessons

a departure

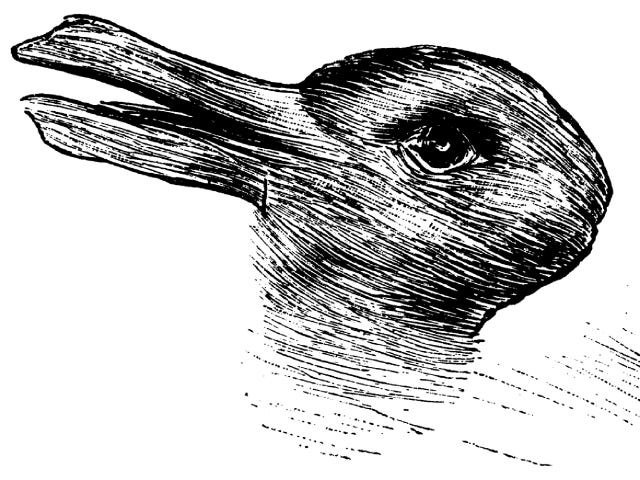

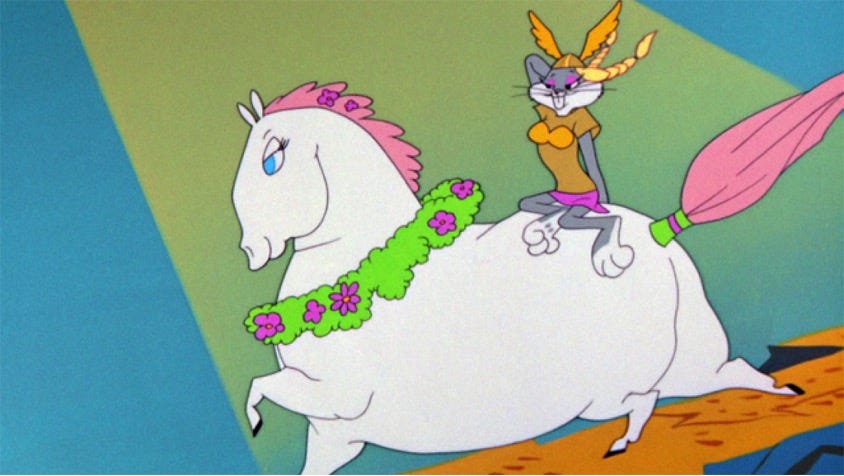

I must admit that I never considered getting a pet rabbit, and probably never would have done so without my wife’s desire to care for a creature whose enclosure she could fastidiously maintain. Hedgehogs and rats were also in the running. I knew very little about rabbits, other than their penchant for cross-dressing, baseball, and Wagnerian opera.

Unfortunately, this combination of ignorance and whim leads many people to adopt rabbits, with bleak consequences. Rabbits are the third most surrendered domestic animal. They’re purchased as Easter gifts for children, their needs are misunderstood, they are left to proliferate, they are abandoned in large numbers by roadsides and parking lots.

The presumption that leads to such neglect seems to be that rabbits are easy – we know what they are (Peter Rabbit, chocolate bunnies, Bugs, children’s toys) and they don’t require much of us other than a cage. The ethical lesson that I learned from Vera, that first and best rabbit, was exactly the opposite. She taught me that the moral opportunity that pets present is—rather than projecting your human desires and motivations and language onto them—to be presented with radically different ways of being, and to attend to them.

She began her life with us in a cardboard carrier with “APPLESAUCE” scrawled on the side in red marker. She ended it in a burnished wooden box, which Maggie and her uncle built together with their hands. We rebuilt our home for her and now we maintain her grave. These are some of the lessons that I learned from her, in between.

Lie to your landlord.

When Maggie and I moved in together, it was into a house that had been divided into a beautiful, regular-sized front unit and another that amounted to a roof over someone’s back porch. We were in the back. It was then that I realized that I had taken for granted that I had spent my life up to that point stepping onto bathroom floors that didn’t have give to them. We were renting this un-air-conditioned shoebox from a classic Bloomington person: she supported NPR, cycled everywhere, probably bought granola in bulk at the co-op grocery store (you know the one), and absolutely never wanted to pay for maintenance. We once asked her if we could have a dog in the apartment and she said yes, under three conditions: it had to be “very small,” if our neighbors ever reported barking we would have to rehome it, and we had to give her $700 up front, non-refundable.

We did not adopt Doug, the enchanting Chihuahua mix at the shelter (though very small he was), but we stopped asking for permission after that.

And so, a few months later, we adopted Vera. When our building eventually was put up for sale and our chaotic landlord was bringing dozens of straight couples unannounced through our apartment every day, we became adept at giving Vera a treat, throwing a big tablecloth over the table under which she lived, and turning on nature sounds to drown out her constant crunching. “Ah yes,” we would say—investors with quarter zips standing six inches away from our contraband lagomorph—“we always put these bird sounds on for our cat.”

Perambulate, then plop.

Rabbits naturally case the joint. When they are allowed to roam freely, they move at first in tentative and angular ways, trying to see the boundaries of their space. No one could hit a 90 degree heel-turn quite like Vera. Rabbits also tend to settle against a corner, so they can perceive incoming threats. In this way, all rabbits are human women. When they finally trust their environment, though, they throw their bodies down with wild abandon, little legs akimbo and teeth showing and tummies toward the sun.

Since the last time I wrote to you, I’ve gone through some major transitions. I moved to Canada. I’m about to defend my doctoral dissertation. I’ve started wearing more earth tones. As wonderful as those changes are, and as happy as I am in my new home, this process is necessarily accompanied by anxiety and fear. What is going to happen? What is my pattern of movement in this utterly new place and time? When will I finally plop? In an especially intense moment of anxiety recently, Maggie reminded me of how brave Vera was. We always travelled with her – to my mom’s house, to Ohio for my top surgery, to Toronto, to the cottage two hours north. She was unflappable, accepting every change and new environment with just a shake of her little rabbit shoulders. After two years with her, we introduced a second rabbit, Leonard, whom she bonded with/dominated in short order.

When she died, we were out of the country at our friends’ wedding. A folklorist pal told me that sometimes animals pass precisely when we are away, as if that could save us the hurt by doing so. I choose to believe this, and that Vera knew exactly what she was doing when she went to another side. It was the last stroke of her bravery, protecting us as we always tried to protect her. I want to be as brave as this rabbit was at 9 years old, running down a hill of black-eyed Susans and clover.

Be overcome.

I guess what I’m interested in, after all, is how pets invade you and your life in ways that you can’t control, ways that don’t end. This is a very good thing. We need not only something that will keep us from thinking about ourselves 24/7, we also need experiences that don’t immediately fit into our existing rubrics. And it’s good for us to have to do things that are mildly annoying, like endlessly vacuuming shed pet hair or constantly purchasing hay (and breaking our fingernails on it). We need to get schooled—why not by a little creature? It’s easier to become prostrate if there’s some terrestrial critter to cuddle at the same time.

Vera invaded my world by changing how I perceive wild rabbits, who are brown-grey like she was. I don’t see them so much in Toronto, but in Bloomington, Indiana, every spring brought with it a glut of baby rabbits. Kits. I used to love watching the adults in their mating dances and boxing matches, and I loved watching the babies take their tentative first hops in the yards with which I was familiar. Once my perception was trained to it, schooled by Vera, I could see not only rabbits running across a road or otherwise hopping past quickly; I could see rabbits resting in the grass with their legs stretched out behind them. I could see wild rabbits chasing each other into what the bunheads call “binkies,” or what my wife and I would call “kick flips,” a way that rabbits throw their wriggling bodies into the air when they’re particularly excited.

Many of my friends have lost their pets in the last few years. Childhood cats aging out, the first dog with your partner passing, senior cats adopted being, indeed, senior. Pet grief is both intense and, often, not taken seriously. Suddenly you must move around your house without that little creature, and every stupid little thing you bought for them is another cut of pain. You keep looking for where they were, where you used to speak out loud to them even though they couldn’t understand. Where they used to snore in the sun – one of the only noises rabbits make.

As hard as this is – as ragged as I still feel writing this now, six months after Vera’s death – isn’t it also beautiful? Isn’t it good to craft a home for a creature with whom you can never truly communicate? Isn’t it fine to be there, with them, in that untranslatable relation?